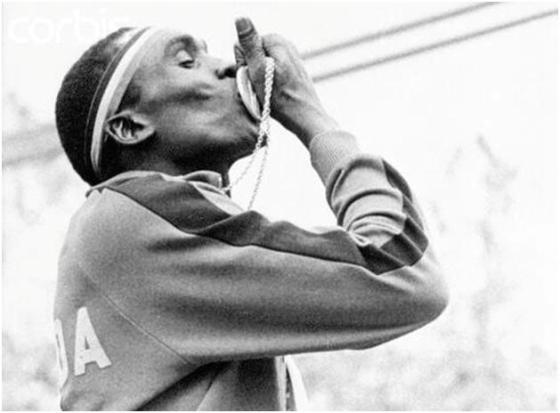

In 1964, an 18-year-old high schooler from Eastern Washington was chosen to represent the US in the 10,000M in a dual meet against the USSR’s powerful distance men. For the first 14 laps he hung in the shadows of the larger Soviets (“I thought it was raining until I realized it was drops of sweat off their brows”). On the 15th(out of 25), his coach yelled at him to take the lead. He sprinted out to a lap of 63 seconds, and continued to pull away from the Soviets, who must have been astonished to have lost to a 5’5”, 118-pound school boy. In an interview after the race, the boy-champion explained why he was compelled on to victory: “I knew people would judge our system by this one race. I couldn’t let America down. I had to do my best.” And it’s quite right that Gerry Lindgren holds himself up as a representative of the American way, since his development as a runner and bizarre career and life afterwards is about as good an example as is out there of how the American free market of sports will occasionally produce athletes of such astounding strangeness, but also quality, that no Soviet (or now Chinese, or really even current American) development program could even think of replicating it.

The main issue with trying to write about Gerry Lindgren is that he reached his running peak ever so slightly before Steve Prefontaine and Nike and Frank Shorter became household names and the press started caring about running, so a significant portion of what we know about Lindgren comes from his own stories, which is problematic because (as you’ll see), he was a pathological liar and con man. That said, he could also run.

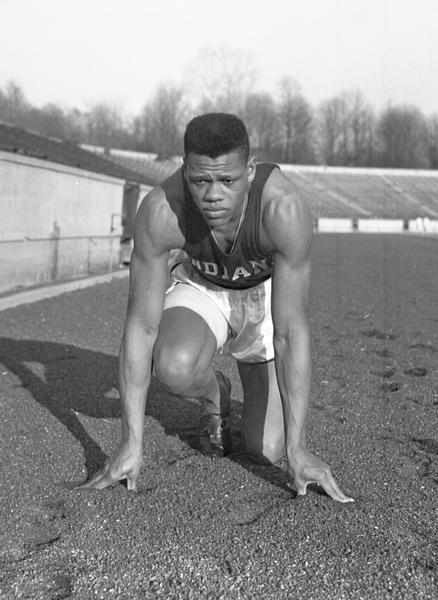

A fairly generous description of Lindgren comes from Sports Illustrated, which claims that “He was jug-eared and had rodent teeth” that matched his “near falsetto” voice. He didn’t run much as a young child in Spokane, but starting right as he hit High School, he decided to start running (cue Forrest Gump music). I’ll let him explain (remember, take this with a few spoonfulls of salt): “I decided if I was going to try to lead these guys [HS cross-country teammates], I couldn’t do it with the wimpy body I had. I was going to have to do more work than everybody else. So I started getting up in the morning and running 5 or 6 miles before school. Just to get a little bit of extra mileage in so maybe I could get my body so it could be as good as anybody else. And then I found if I got up at 1 a.m. or 2 a.m., I could do 10 miles then go back and sleep until I had to get up in the morning. So I was running three times a day like that during my last two years. By the time I was a senior in high school, my legs didn’t get tired. I could run too fast at the start of a race and still run well, but I could do it because and it didn’t bother me that much because my legs didn’t get that tired.”

Which prompts the question – how much training did you actually do? “We never counted miles back then and never did have any idea until Ron Clarke was writing his book. After I met him in San Francisco, he asked me how many miles a day I was running. And it was such an unusual question because I had never thought about that. I tried to add up miles and at some point I got to about 40 miles per day on some days and he said, ‘No, that’s not right, that’s way too many.’ So he went to my coach and asked the same question and, of course, he didn’t know either. I was doing the morning and nighttime workouts on my own. Nobody really knew about them. During that stretch, he figured I was doing all of these extra workouts, so he tried to count them out, too. And he got the same numbers 40 miles per day, too Clarke said that’s impossible, so he wrote 25-35 miles a day in his book.”

Now, some of you are probably thinking “That’s a lot of time to be running, and that means he had no time to do other things” — the rest of you vastly overestimate the number of things there are to do in Eastern Washington (Zing! Sorry, eastern side of the state). But seriously, all of this stuff is pretty unbelievable (like, in the “I think you’re bullshitting” meaning of the word). But then when he was 17 he went out and ran a US high school 2-mile indoor record in 8:40. That record stood through Ryun and Prefontaine and Webb and Verzbicas until Edward Cheserek broke it earlier this year. What’s even cooler about that race is that he didn’t get pulled along to a good time in a stacked race (yep, I’m looking at you Alan Webb) – he was facing the best runner in the world (Ron Clarke) and ran out into the lead, which he hung onto for a while, but ultimately got passed. That’s the way he always ran – from the front – which I think makes sense in a deeper way (see footnote for my psychoanalysis)*

*Tangent: It seems to me like there are basically two types of runners – those that run fastest when they are chasing somebody, and those who run better being chased. Now, oftentimes we say the runner who goes out hardest is the more confident one – he’s challenging the field, “Catch me if you can”. Think about all the silly inspirational Prefontaine posters you see in the Nike stores. But if I think about the famous frontrunners (Lindgren, Prefontaine, and really Frank Shorter too, who said (at least through the 1972 olympics) that he’d never lost a race when he had broken away into a lead), they are often the least confident runners. They see themselves as prey, with the world always out to get them. They’re the paranoids, driven forward not by any real threat to their winning the race, but by the fear of what might be behind them. The kickers are the ones with supreme confidence – “no matter who you put out there, I will catch him”. Well, the victim mentality makes sense for all these runners (side note – I’m about to make a bold an probably offensive assertion as relates to abuse): Prefontaine was always mocked for not speaking English (his first language was German) and being so small; Shorter was actually physically abused by his father growing up (yep, there it is…, though worth noting that Lindgren’s father also drank and beat him (beat Lindgren, that is, not Shorter…or himself)); and Lindgren, well, you can tell from the above that he saw himself as being weaker than everybody else (another quote: “I was filled with all these lemons,” he said. “I was scrawny, weak and dumb. I just wanted to show that even of these I could make lemonade.”) The victim mentality permeates every interview Lindgren gives (NB: His father also drank and beat him). Prefontaine started to hide his behind an external confidence, but it was always there. Anyhow, tangent over for now.

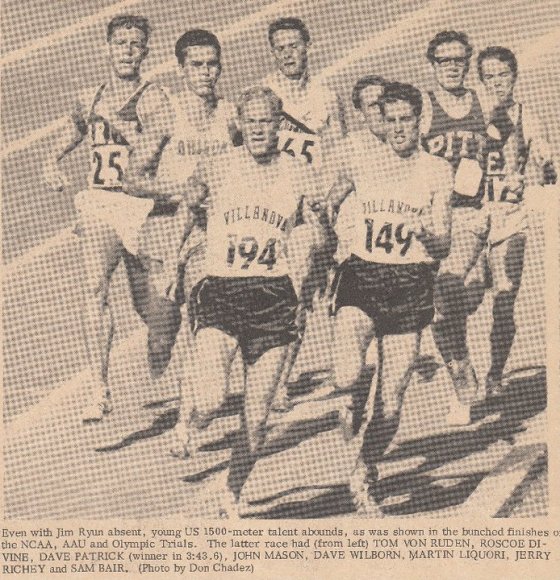

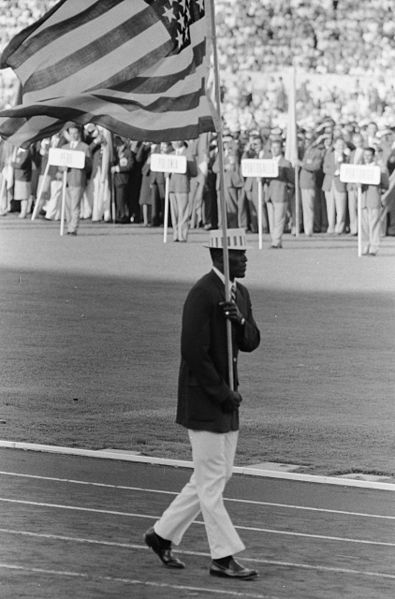

Lindgren continued to improve, and put on a race in the summer of 1965 against Olympic 10,000 meter champion Bill Mills (Look at Mills! Look at Mills! Still the most spine-tingling call of a race, for my money). Unfortunately, Lindgren had injured his ankle in a car accident two weeks before, and didn’t know if he could run. Well, he ran, and stayed with Mills stride for stride, finishing next to him with a dual world record of 27:11. Lindgren went off to Washington State for college (he kind of wanted to go to Oregon, but the Oregon coaches thought WSU would be better for him academically), where he had a solid career, highlighted by an incredibly narrow win in the NCAA cross-country championships over Freshman Steve Prefontaine (In the race pictured above). Lindgren remained competitive, but was always injured during the run-up to the Olympics, so never hit the highest highs that other major runners did. In the late 1960’s, he was drafted, and was stationed at Fort Lewis with Kenny Moore (whom most of you know by now…).

And that’s when things get a bit weird.

Lindgren spent some time in the early 1970’s working for Glenn Turner’s “Dare to be great”, which was a sort of nutritional/cosmetics pyramid scheme that ultimately earned Turner $44 Million (which he was later forced to repay) and a 7-year prison sentence (which he was permitted to keep). Lindgren got married and had a kid or two, and then, in January of 1980, he just up and vanished like a fart in the wind. It should be noted that he had some legal issues at the time, but fairly minor ones – mostly just failure to pay child support for a child he claims wasn’t his (“I never met her!”).

Nobody really knew where he went. People assumed he was safe because he left a note for his wife saying that she could do what she wanted with their business (a running store called The Stinky Foot). There were some rumors that he was living in Hawaii under an assumed name. As it turned out, he probably went to Houston and worked at Burger King (Where he as Manager of the Year!). After a couple years, Kenny Moore heard from a University of Hawaii runner that Lindgren was selling shoes out of a shopping cart in Hawaii, living under the name Gale Young. Moore tracked down a phone number and called (following words from Moore’s Sports Illustrated Article):

The voice on the phone dropped into a keening wail of what seemed recognition and then said hesitantly, “No, no, I think…I think you probably have the wrong guy.”

“I knew it was Lindgren. He went on in a rush about how he occasionally was mistaken for that runner, what was his name? Boy, he wished he could run like he heard that guy could run….

And then, suddenly, he was speaking to me in his natural voice. “You just over for the marathon? Things in Eugene the same?” That lasted for a few sentences, then the first, strained tone cut back in. “No, no,” he said. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I hope you find the guy you’re looking for but I’m not him.”

But then five years went by, and Moore actually moved to Hawaii and called up a person he thought to be Lindgren (who answered in a “mock-oriental” voice), who claimed he didn’t know Lindgren, but who then immediately called back as Lindgren, and decided to join Moore for dinner. This was in 1987ish. Moore actually started talking to him and basically convinced him to return to the real world. He ran in a legends mile in Oregon in 1987 (along with Jim Ryun). It’s hard to say he got a hero’s welcome, because, I mean, he abandoned his wife and child and I think still hasn’t spoken with them. But I guess people were glad to have him back. Then he basically rejoined normal life. There is a long 20 part interview with him on youtube that gives you a taste of how strange he can be. He spent a few years coaching the University of Hawaii women’s track team. But basically, his bizarre tale ends with a bit of a whimper, which in some ways makes it more bizarre. He popped up briefly when Verzbicas and Cheserek were chasing his two-mile record, but otherwise seems to be living a somewhat standard under-the-radar life.

So, if you’re keeping track, there were three high-school runners in the 1960’s who remain, probably, the three best American HS runners of all time: Steve Prefontaine got the Achilles treatment of glory and an early death, Jim Ryun became a six-term US Congressman, and Gerry Lindgren… became manager of the year at a Houston Burger King while living under an assumed name, having abandoned his wife and child.

Runners are weird.

Extra note that is worth reading, but doesn’t really fit in this post: I’ve been writing little snippets of this for a few weeks, but keep turning it over in my head because it’s absolutely bizarre and I feel weird writing about it for the same reason writers never knew how to write about Bobby Fischer, and how some obituaries of David Foster Wallace seemed strange. Which is to say, how do you treat a subject who is almost for sure a genius (of some kind, and I get that each is a very different kind of genius, with Fischer and Gerry Lindgren being far more similar to each other than either to Wallace), but also almost for sure mentally ill (a big step to say that about Lindgren, less so of the others), and for whom that mental illness / paranoia was almost surely inextricably linked to the genius? In our fictional stories, this is often what we want – a tragedy is so much more compelling if the trait that leads to success leads also to the downfall, than if the two are separate. With Wallace you can see in his writing the fact that his brain never stops, and while it can be entertaining to read, you constantly feel that it would be absolute pain to live with a Brain that never rested, and never stopped questioning. Fischer was smart, but he was also the hardest working chess player of all time, driven by a paranoia. To win at chess, you have to be constantly assuming that your opponent is out to get you, and that there are threats that you can’t see and have to keep looking for. It’s not hard (whether correctly or incorrectly) to see the parallels to his later paranoia (when he constantly spouted anti-semitic conspiracy theories about everybody who was out to “get him”)**. With Lindgren? I don’t know.

**[Double tangent: 1) As a former amateur chess player, who got just good enough to peer into the abyss of what actually being good at chess meant, I think they are 100% related, and 2) Vladimir Nabokov created this exact scenario in his book “The Defense” (sometimes “The Luzhin Defense”) which was written well before Fischer was born, and in which the lead character is a grandmaster who slowly blurs the line between the chess and real worlds, comes back out of this mental illness briefly, then gets sucked back in to the point that he loses the ability to differentiate between his life and a chess game, and leaps to his death mid-chess-game (and mid life-game) in order to abandon it (and it)]. So anyways, yeah. Let me know if you’re interested in signing on for a weekly Chess e-mail, too. Paul Morphy used to eat only food that was prepared by his mother! How about that!

Ben